We have assembled a list of our commonly asked questions that are asked in most areas.

Why can aircraft fly at sensitive times?

Aviation is a vital industry for the Australian economy. Business, tourism, social and freight activities rely on aviation. Unlike many other industries, aviation is regulated by the federal government rather than by state governments. This makes aircraft noise regulation quite different from the type of noise regulation you are used to at a local level that might, for example, prohibit noisy activities before 8:00 am on a Sunday.

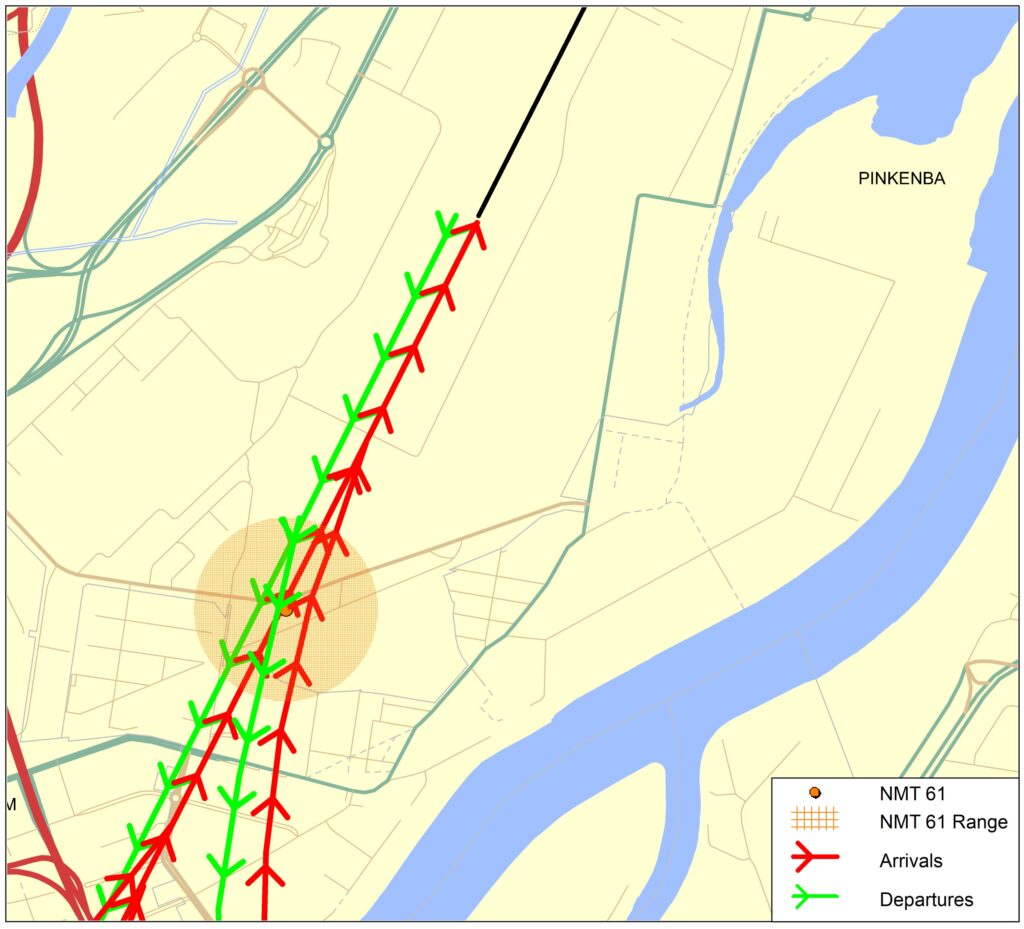

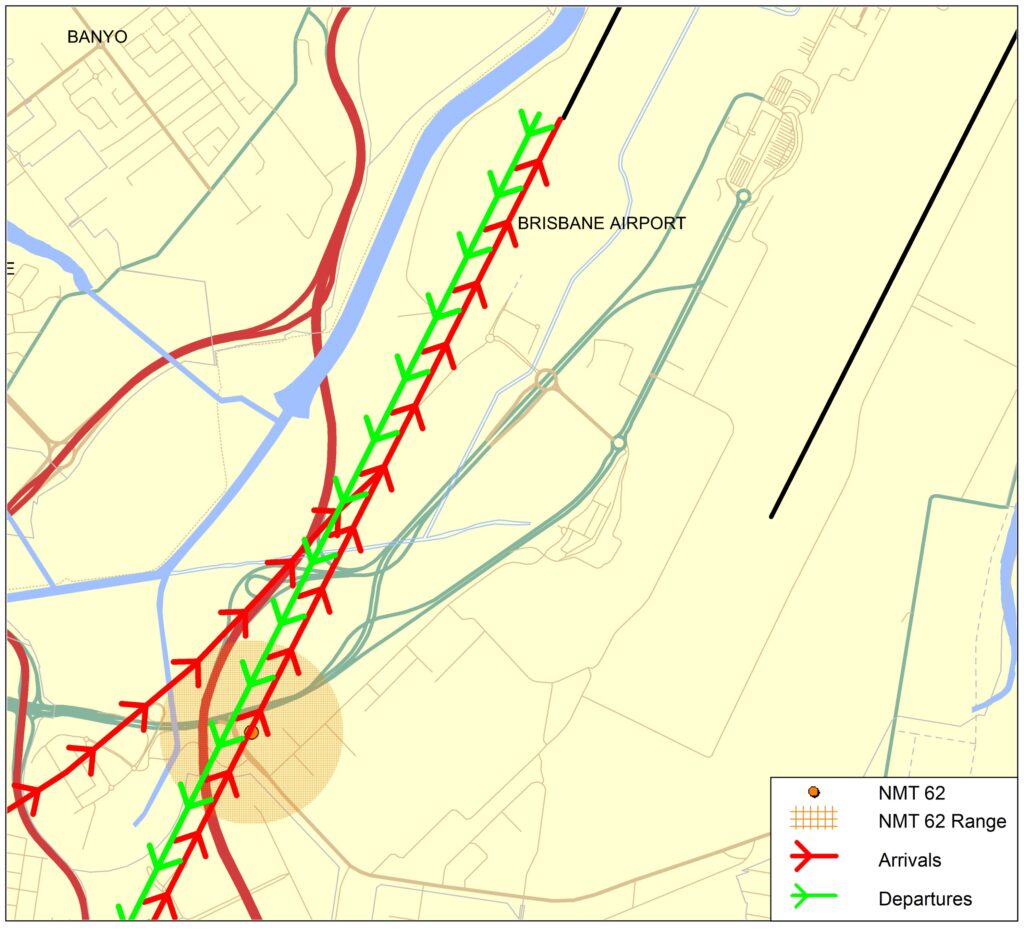

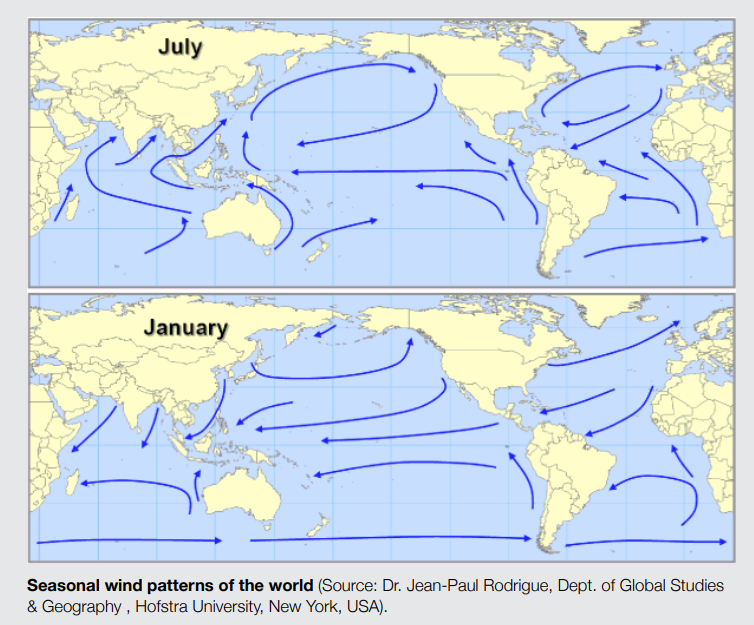

Major airports in Australia are situated very close to residential areas and for this reason it is not possible to design flight paths that avoid flying over homes. In cities where the airport is located on the coast, flight paths will be designed to fly over water wherever possible. However because aircraft must take off and land into the wind, it is not always possible to avoid flying over residential suburbs by staying over water.

Aircraft noise remains a key challenge for an industry that is forecasting high levels of growth in air traffic movements over the next 20 years. Managing noise impacts on communities requires careful balance between the protection of affected residents and recognition of the broader economic and social contributions of the aviation activity.

Why can’t the flight paths be moved away from me?

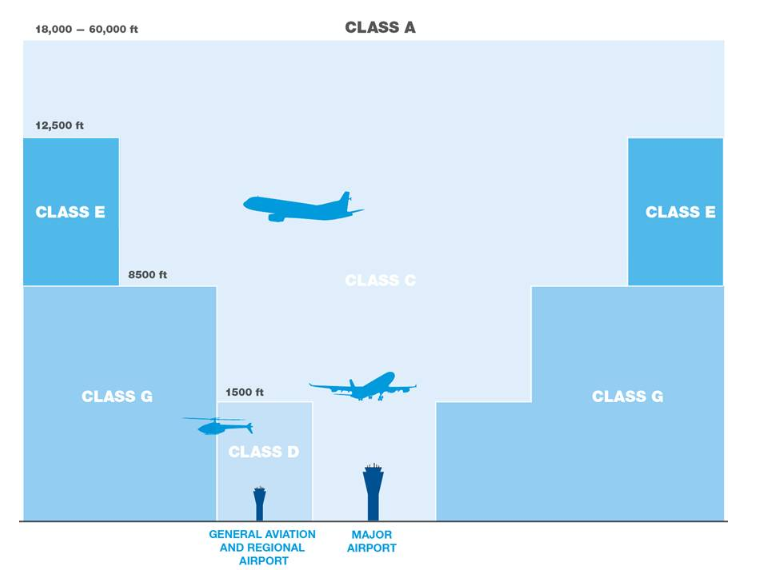

Flight path design is a complex process. Flight paths must comply with international design standards and Australian safety regulations. Changes to flight paths may be made for a variety of reasons, including safety and noise management. However, changes are not easy to make as changes to one flight path usually impact other flight paths.

In considering any change, first of all we must have regard to safety – any change that could compromise safety cannot be progressed. Managing aircraft in a regular way and minimising complexities are central tenets of safety. We also consider the efficient operations of the airport and whether there would be an overall noise improvement for the community. We do not generally consider that moving noise from one part of the community to another is a noise improvement. In considering this we have to have regard to the entire flight path and the fact that moving it at one point may result in adverse effects many kilometres away. Unfortunately, the reality is that it is very difficult to identify flight path changes in metropolitan areas that can be made without moving the noise, or compromising safety or efficiency.

If a potential change is identified it must be environmentally assessed, the community, including potentially affected areas, the airlines and other stakeholders must be consulted and feedback from all must be considered. Finally, if the change is to go ahead, aeronautical documents for pilots must be produced and published and time allowed for crews and air traffic controllers to be trained in the new procedures. All these requirements mean that changes can take several years to make.