Fly Neighbourly Advice or Fly Neighbourly Agreements are voluntary agreements established between aircraft operators and communities or authorities (normally airports or local councils) to assist in reducing the impact of aircraft noise on local communities. Archerfield Airport has a voluntary Fly Neighbourly program, which encourages pilots to fly in a noise sensitive way whenever possible.

Brisbane Airport noise abatement

Noise Abatement Procedures

Every major airport has Noise Abatement Procedures (NAPs), which are procedures designed to reduce the impact of aircraft noise on the community. There are some limitations to the use of NAPs and they may not be used if they generate delay and congestion, as this can cause noise and emission impacts. Air traffic control or pilots may not be able to use them in certain situations, for example weather conditions or operational requirements.

The main Noise Abatement Procedures currently in use at Brisbane Airport are:

Preferred runways

Air traffic control nominates the runway for use to ensure safety and operational requirements are met, depending on the weather conditions. If weather conditions do not favour a specific runway, the ‘preferred’ runway is used, two of the main points are set out below.

- From 6 am to 10 pm, providing wind and traffic management safety requirements permit, arrivals over Moreton Bay and departures over Brisbane suburbs from Runway 19 L/R is the preferred option.

- From 10 pm to 6 am, providing wind and traffic management safety requirements permit, Simultaneous Opposite Direction Parallel Runway Operations (SODPROPS) are used to enable aircraft to depart and land over Moreton Bay, arrivals onto Runway 19R and departures on Runway 01R.

If the downwind in the southerly direction exceeds 5 knots or there is downwind and the surface is wet, to comply with runway selection criteria, northerly runway direction operations will be nominated. Aircraft will then land over the city and depart over the bay. If conditions change quickly and the forecast suggests it may continue to change, a change of runway direction may not occur immediately or at all, if our air traffic controllers are satisfied that the runway selection criteria is adhered to.

Reciprocal runway operations

During night operations (10 pm to 6 am) Simultaneous Opposite Direction Parallel Runway Operations (SODPROPS) is the preferred operating mode. SODPROPS sees all aircraft operate over the bay by using one runway for departures and the other for arrivals.

To operate SODPROPS visibility must be eight kilometres or greater, the cloud base must be 2500 feet or higher, the downwind must be less than 5 knots and the runway surfaces must be dry.

If SODPROPS cannot be used, the NAPs specify that the southern end of the new runway should not be used during the night period.

Using SODPROPS during day operations

SODPROPS sees all aircraft operate in the same airspace. This means aircraft are ascending and descending in the same airspace and regularly crossing flight paths. This complexity prohibits the use of SODPROPS during busy periods which tends to be throughout the day period. Our air traffic controllers will use SODPROPS during day operations when possible however the traffic density often precludes this. At this time, while traffic numbers are lower than expected, we tend to see the SODPROPS mode maintained after 6am and commence prior to 10pm.

Intersection departures

The NAPs specify that aircraft heavier than 30 000 kilograms cannot use an intersection departure, except when complying with certain ICAO requirements.

Any aircraft below this weight can use an intersection departure and will do so if necessary.

Intersection departures are not permitted by any aircraft between 10pm and 6am, with the exception of a limited number of turbo-prop aircraft from 5am.

Temporary NAP

We will implement a temporary Noise Abatement Procedure to adjust the turbo-prop traffic spread to match what would have been experienced had COVID-19 not affected traffic volumes. This will increase operations in the areas between the short and long approaches (the swathe) during periods of high demand, while the shorter visual approach will still occur when traffic volumes are generally lower.

This temporary procedure will be in place until operations increase to both runways, which will then result in a similar traffic management outcome – with more aircraft operating within the ‘swathes’.

Learn more about turbo-prop operations during COVID-19 on our How do turbo-prop aircraft fly? page.

How much noise are aircraft allowed to make?

In Australia, aircraft noise standards apply before an aircraft is allowed to operate here, rather than in the course of its day-to-day flying activities.

Before an aircraft begins operating in Australia it is required to meet international noise standards that specify the amount of noise that may be emitted by that type or model of aircraft. If an aircraft does not pass the certification process, it may not fly in Australia. However once an aircraft passes this certification process, there is no legislation or regulation that enables any agency, including Airservices, to police its noise levels.

There is no regulated maximum noise level for aircraft flying over residential areas. Without any maximum level set out in legislation or regulation, there is no objective measure to determine whether any aircraft flying in Australia is “too noisy”, or whether the combined load of aircraft experienced by a community is “too much” noise.

More information about Aircraft Noise Regulations is available on the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications website.

What are the rules about helicopters?

Helicopter routes

While helicopter routes exist, helicopters are not restricted to these routes. Inside controlled airspace helicopters must comply with directions from air traffic control whether flying on or off established routes. Outside controlled airspace aircraft, including helicopters, are not under the direction of air traffic control but they must comply with aviation regulations set down by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

Altitudes

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority have regulations for how low aircraft, including helicopters, can fly. These regulations require helicopter pilots fly no lower than 1,000 feet (ft) over built-up areas, or 500 ft over any other areas, unless they are landing or taking off.

Helicopters can fly below these heights in certain situations – for example, police, rescue, fire fighting and military helicopters may fly at any height required.

More information is available on the CASA website.

Hovering

There are no regulations or legislation that prevent helicopters from hovering over an area. For example, media helicopters are permitted to hover while covering a story or sporting event.

If a helicopter pilot wants to cross a ‘controlled’ zone around an airport, it is sometimes necessary for air traffic control to hold the helicopter in one place until it is safe to cross. This sometimes means helicopters have to hover over built up areas.

Who makes decisions about aviation?

Responsibility for aviation operations is shared between a range of parties including Airservices, other federal government agencies, airlines and operators, pilots, airports and state and local governments.

AIRSERVICES AUSTRALIA (AIRSERVICES)

Airservices is Australia’s civil Air Navigation Service Provider (ANSP) to the aviation industry and provides aviation rescue firefighting services at 27 of Australia’s busiest airports. Airservices is a corporate Commonwealth entity established and governed by the Air Services Act 1995. Airservices publishes aeronautical data, maintains aviation telecommunication infrastructure and radio navigation aids, updates flight procedures and provides a national aircraft Noise Complaints and Information Service (NCIS).

AIRPORT OPERATORS

Airport operators are the decision-makers for all on-airport activities, including developing infrastructure to support aircraft operations, such as new runways, and safeguarding aviation operations. Airport operators may also develop noise management plans, limit aircraft movements, encourage quieter fleets, prepare long-term forecasting of aircraft noise around the airport, such as the Australian Noise Exposure Forecast (ANEF), and manage local community engagement.

AIRCRAFT OPERATORS

Aircraft operators are responsible for what is referred to as “noise at source”. They make decisions about what type of aircraft they operate, what engines they equip aircraft with, and which airports they fly those aircraft to. Aircraft operators can also modify aircraft to reduce noise impacts and invest in newer fleets. All these factors can impact the noise experienced on the ground.

CIVIL AVIATION SAFETY AUTHORITY (CASA)

The Civil Aviation Authority (CASA) is a government body that regulates Australian aviation safety. It sets rules that pilots, aircraft operators, air traffic controllers and airports must comply with. CASA validates the instrument flight procedures Airservices produces and is the ultimate approver of Airspace Change Proposals.

DEPARTMENT OF INFRASTRUCTURE, TRANSPORT, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT, COMMUNICATIONS AND THE ARTS

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts (the Department) is responsible for administering Minister approval of airport infrastructure projects for federally leased airports, generally submitted through a Major Development Plan (MDP) and Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), and for providing policy advice to the Minister on the efficient management of Australian airspace and aircraft noise and emissions. The Department can make recommendations to the Government on regulatory measures to manage aircraft noise. This department is also responsible for setting the requirement for federally leased airports to produce an ANEF.

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) administers the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and is involved in assessing any proposed changes to aircraft operations that trigger “significance” under this Act. The Commonwealth Minister for Environment provides advice on these changes.

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE

The Department of Defence is responsible for aircraft operations by military aircraft at military-controlled airports. They provide information, undertake community engagement and are responsible for managing complaints about military aircraft noise.

STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT

State, Territory and Local Governments are responsible for land use planning around airports through zoning, subdivision control, and comprehensive planning actions. Local Governments may also be airport owners.

AIRCRAFT NOISE OMBUDSMAN

The Aircraft Noise Ombudsman conducts independent administrative reviews of Airservices and Department of Defence management of aircraft noise-related activities.

Do planes have to stay on flight paths?

What is a flight path?

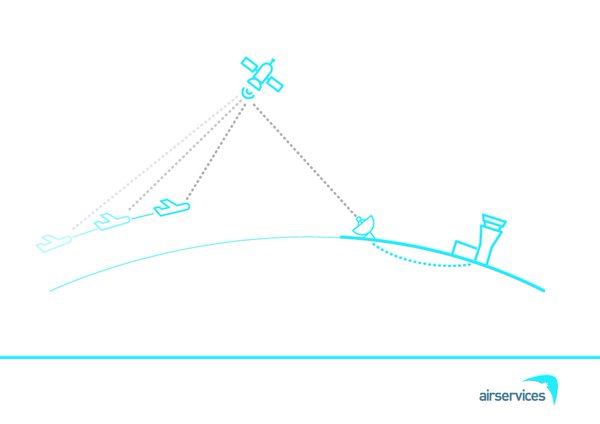

The term ‘flight path’ is used to refer to the mapped three-dimensional corridor where aircraft fly most of the time. Flight paths can be a number of kilometres wide, rather than the single lines depicted on flight charts (maps). Aircraft may fly differently within these corridors for a range of reasons, including aircraft performance (including type, speed and weight), and navigation systems.

Aircraft may deviate from flight paths for a range of reasons, including weather and operational requirements. In controlled airspace, this will be at the approval of air traffic control (ATC).

Weather diversions

During periods of bad weather aircraft may need to be diverted off the normal flight paths to avoid storm cells, heavy rain and dangerous cloud formations. Sometimes this bad weather is not in your local area but it can be detected many nautical miles away by sophisticated weather radar systems that are installed in modern aircraft. If a pilot requests a diversion to avoid bad weather this will be facilitated by air traffic control. This can result in aircraft flying outside the published flight paths.

Traffic management

Sometimes air traffic controllers need to take aircraft off the published flight path in order to ensure that safe separation is maintained between aircraft. For example, this might occur when the volume of traffic in the airspace is high, such as during peak periods, or it might occur when a jet is flying behind a slower turbo-prop aircraft. The slower plane may need to be turned off the flight path so as not to delay the faster jet. This can result in aircraft flying outside the expected paths.

Missed approaches

A go-around, or missed approach (also sometimes referred to as an aborted landing), is a safe and well-practiced manoeuvre that sees an aircraft discontinue its approach to the runway when landing. This standard manoeuvre does not constitute any sort of emergency or threat to safety. It will however result in the aircraft flying an unusual flight path as it climbs and circles around for another approach.

The most common cause of go-arounds is adverse weather conditions, including strong winds, experienced by the aircraft on final approach. Debris on the runway, an aircraft (or vehicle) that has not yet cleared the runway or an aircraft that has been slow to take-off may also prompt go-arounds.

Emergency services operations

The published flight paths may be varied to avoid disruption to high priority emergency aircraft including aircraft involved in fighting bush fires, search and rescue, medical or police operations.

Light aircraft and helicopters

Generally, published flight paths are for aircraft flying according to Instrument Flight Rules (IFR), which is where the pilot uses instruments to fly.

Helicopters and light aircraft often fly Visual Flight Rules (VFR) where the pilot uses visual references to the ground or water and does not fly on a set flight path.

What are the rules about altitudes?

The altitudes of aircraft over your area can vary according to:

- the airport the flight is coming from or going to

- whether the aircraft is coming in to land, taking off or in level flight

- the specific requirements of the flight path

- the need for air traffic control to maintain vertical separation between aircraft.

There are no regulations setting out minimum altitudes for aircraft in the course of taking off or landing at an airport.

Variation in departure altitudes

You may observe differences in the altitudes of departing aircraft. Aircraft have different climbing abilities depending on factors such as the type of aircraft and its weight, how heavily laden it is, and even the meteorological conditions at the time.

Large jets such as Airbus A380s will climb more slowly than smaller, lighter aircraft because they are so much heavier. A380s are frequently used for long-haul non-stop flights and in these circumstances will be fully laden with fuel. This adds to the weight and further compromises climb performance. When two aircraft of the same type are observed to have different climb rates this is usually because one is heading for a closer destination than the other, and is therefore carrying less fuel weight.

Atmospheric conditions can affect climb rates. For example, when it is hot and humid the air is less dense. This affects the “lift” of an aircraft and it will take longer to climb in these conditions.

Minimum altitude for level flight

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority have regulations for how low aircraft can fly. These regulations require pilots fly no lower than 1,000 feet (ft) over built-up areas, or 500 feet over any other areas, unless they are landing or taking off.

Aircraft may be able to fly below these heights in certain situations. More information is available on the CASA website.